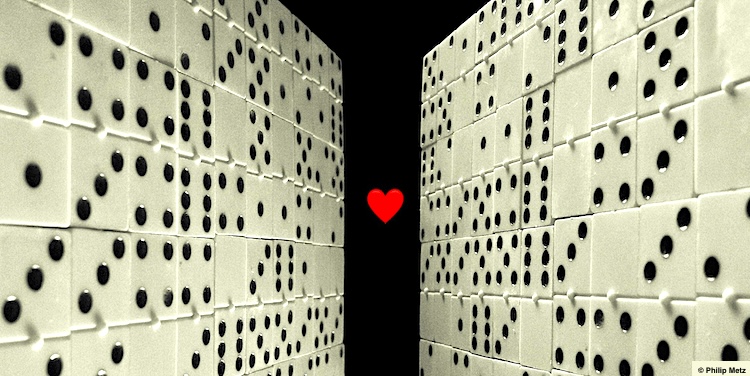

This week, PIPOL 12 offers us a kaleidoscope — a kaleidoscope of discontents within the family.

Georges Didi-Huberman [1] reminds us that the kaleidoscope, also known as a “transfigurator,” was invented in 1817. He also notes that what is placed in the tube, allowing, with each rotation, the visualization of a new facet, belongs to the realm of waste, dispersal. Indeed, these are bits of fabric, tiny shells, dust, materials that are each time scattered and each time rearranged through the play of mirrors and the rotation of the tube in our hands. And this enchants us.

How are the components of the family and the modalities of discontent articulated in the texts we are about to read? Hasn’t the delicate yet vivid institution of the family — whose “essence and not […] accident […] is the reining in of jouissance” [2] — always harbored a fundamental unease? From this ever-shifting juxtaposition, what images can emerge, which each time synthesize the elements into a new configuration ?

For Lévi-Strauss, the family is an invariant, a universal structure of human societies. Katty Langelez-Stevens calls it “the first human institution [3].” Marie-Hélène Brousse raises a question : does the secret, an obligatory and long-standing point in the family — “there is no family without a secret” — differ in the context of today’s malaise ?

With Gaëlle Chamboncel, the kaleidoscope reveals the break-in of a Real that cannot be spoken. In the series Icon of French Cinema, it takes the form of the bad encounter, resulting in a shift from desire to “an injunction of jouissance.”

The family is united by a “non-dit” (an unspoken) : “What is the jouissance of the father and the mother?” [4] It is inside the torment of the film The Zone of Interest that Nelson Hellmanzik invites us to bravely plunge our gaze toward “something impossible to see”.

“His mother stuffs him with food and penetrates him with English words,” writes Fabrice Ferry. This is what Louis Wolfson spent his life fighting against, showing that it is not family stories that get passed down, but debris and waste charged with jouissance, with which the subject must cope.

For a subject whose familial tale cannot be spoken or dialecticized, Cristóbal Farriol wagers that “an institution supporting the hypothesis of the unconscious” allows this subject, in transference, to come to the end of “the non-writing of his story.”

Emilia Cecce points out that, in the face of the societal changes, the family institution stands as an indispensable core of support. In what ways can the analyst, through transference, become a partner to families, user associations, or mutual aid organizations ?

Like a kaleidoscope, this newsletter — combining secrets, “non-dits”, family stories, the familial tale, and jouissance — brings forth new configurations.

Enjoy the discovery !

[1] Didi-Huberman, G. “Connaissance par le kaléidoscope,” Études photographiques, May 7, 2000. Available online.

[2] Lacan, J., “Allocution sur les psychoses de l’enfant”, Autres écrits, Paris, Seuil, 2001, p. 364. In English : “Address on Child Psychosis”, translated from the French by A. Price & B. Khiara-Foxton, Hurly-Burly No 8, 2012, p.272.

[3] Langelez-Stevens, K., PIPOL 12 Argument, available on the blog.

[4] Miller, J.-A., “Family Affairs in the Unconscious,” La Lettre mensuelle, no. 250, July–August 2006, p. 9. In English : « Affairs of the Family in the Unconscious », translated by F.-C. Baitinger and & A. Khan, The Lacanian Review No 4, 2018, p.74.

Translation : Laurence Maman

Proofreading : Alasdair Duncan